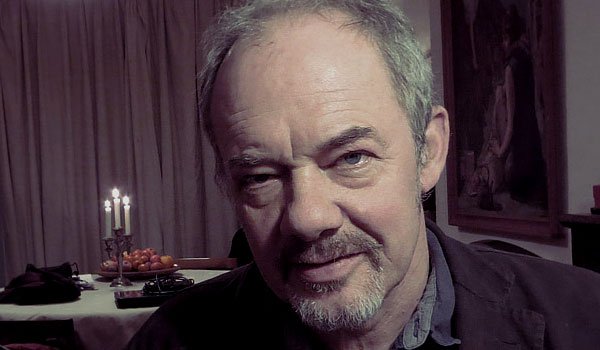

This controversial film exposing the war crimes and massacres committed at the end of the civil war in 2009 has been effectively banned in Sri Lanka until now – and anyone helping the film-makers threatened with prosecution. The announcement coincides with the visit of new Sri Lankan President Maithripala Sirisena to the UK and takes place the day before he is due to have dinner with the Queen. The release of the film in Sri Lanka will allow the majority Sinhala population to see for the first time the shocking evidence of war crimes and massacres committed at the end of the war by their own government’s forces, said Director Callum Macrae in an exclusive interview with JDS.

Until now the vast majority in Sri Lanka, particularly the Sinhala people have been denied the truth. The new government has repeatedly undertaken to transform the media situation and open up media freedom including lifting the ban on the internet. In this environment we are offering this film to the Sinhalese people of Sri Lanka, with trust and hope that when we release this the government will allow the Sinhala people to watch this and know the truth without any hindrance. We hope that it will help open up a national conversation for peace and justice which will pave the way to a long lasting political solution.

What are you going to achieve that you have not achieved in other languages?

Alongside Tamils and Muslims the Sinhalese people have shown that they were absolutely rejecting the corruption, the nepotism, the oppression and the white van kidnappings of the previous regime. That is a huge change. I don’t play it down at all. This is a very brave and significant stand that the people of Sri Lanka have taken.

Now they have go to the next stage. These are probably more important. They are existential issues for Sri Lanka. That is the search for truth and justice for what happened during the war. That search is very important so that there can be democratic and political solutions that will guarantee the democratic rights of all the people in Sri Lanka so that they can live in peace. The Sinhalese have a vital role to play in that. But it is difficult to play that role if they don’t know what happened in the war. That is where ‘No Fire Zone’ in Sinhala will be helpful.

But your film accuses Sinhalese for the crimes committed.....

Sinhala people have suffered during the last 30 years from attacks by Tamil Tigers. But also, Sinhala people have suffered attacks from the state. Killings and disappearances are part of the recent history of Sri Lanka. One of the key issues that the Sinhala people will want to address is the whole culture of impunity which in the past has been turned on certain significant sections of them. If that culture of impunity is addressed it will be beneficial for all those in Sri Lanka as a whole to find a way forward.

During a whirlwind series of recent meetings in New York and Washington Macrae met senior policy makers, ambassadors and others from the US government and the UN. He also gave a presentation and showed clips from the latest version of No Fire Zone to a series of meetings including a congressional round-table attended by senior policy makers, staffers as well as politicians and former diplomats. JDS asked him about the US policy towards Sri Lanka since Maithripala Sirisena was voted into office.

I think it is quite important what is going on in America. Previously, America spoke broadly with a united voice, in terms of the need for justice, truth and accountability. The new Maithripala Sirisena government is certainly to be welcome. Nonetheless, it has led to a changing of the position to some extent in America. I regard this as a cause of concern.

Earlier, United States spoke with a united voice. Partly, that is because there were voices coming from the military, voices representing America’s geo-strategic interest, who were happy to go along with the argument of human rights. Because, they were in a way something you can attack and criticize the Rajapaksa government in which they were losing faith.

Primarily, it was due to the growing relationship with China. Because the new Maithripala-Ranil government is to quite an extent moving westward by recreating its alliances with the west and India, while moving away from China, there are elements in the US who represent strategic and military interests who say ‘ah well, that’s alright, then’. Some people have specifically said, ‘let’s lower our voices on human rights’. So, that is a concern. The argument I heard from sections of America is that this new government should be given time to consolidate, establish itself and to make initial reform.

Three dynamics

There are three dynamics going on in Sri Lanka which influence the policies of the Sirisena government.

First, it is international pressure. The re alignment with the west and India can offer benefits for Sri Lanka. These benefits can be used to influence Sri Lanka to keep it pursuing truth and justice and to keep it seriously moving towards finding a political solution.

Secondly, the Sirisena government fundamentally does not consider itself answerable to the Tamils and Muslims who elected it. It considers itself answerable only to the Sinhala constituency. The Sinhala constituency is by and large still motivated by the same kind of chauvinism, ultra-nationalism and paranoia that was encouraged by the Rajapaksa regime.

Thirdly, the Sirisena government is itself compromised. Most of the newly appointed military leaders as we have seen by the recent JDS article, were implicated in what happened during the war. Although, General Sarath Fonseka has been marginalized to some extent, he is clearly implicated. Sirisena himself was the acting commander in the absence of Mahinda Rajapaksa. In itself, he might have some excuse in an international court where he could say, ‘technically, I was doing that, but really, I was not that influential’. What Sirisena had done in his election campaign is the very opposite. He said, ‘I was in charge’. He boasted that fact, putting himself straightforwardly in the frame of those who were responsible for what happened at the end of the war.

So, the pressure from their own constituency and the complicity of the Sirisena government and so many people in it, will push the government towards not confronting the issues of justice and truth over the war crimes and the massacres. They will also push to not confront the very profound issues which must be addressed with extreme urgency. That is finding political solutions for injustices that have divided Sri Lanka since independence.

If the first dynamic which is the international community takes the pressure off, then those two other dynamics will overwhelm the Sirisena government. So, it is absolutely essential that the international community maintains the pressure. Taking the pressure off is a recipe for disaster.

So why are they taking the pressure off?

They are, understandably, elated and happy about the very important changes that the Sirisena government are working towards. Sri Lanka was sinking dangerously towards something actually like fascism, with the racism, the triumphalism, the chauvinism, the corruption, the repression, the disappearances and the sheer terror. Significant steps have been taken towards arresting that process. That is clearly welcome by everybody. That’s one reason, which is a good motivation. But, my impression is that the government is re introducing democracy only for the Sinhalese. But, not for the Tamils.

The second reason is that not all the pressure for human rights is as honorably motivated as it may appear. And some of the human rights issues were undoubtedly used to bash the Rajapaksa regime over the head as it became increasingly embarrassing to the west and increasingly aligned itself with China.

Macrae says that it is not the Rajapaksa regime alone that is to be blamed for what happened in the war. He is of the view that there is a structural problem in Sri Lanka and it should be solved by the people of the country collectively to find the way forward. ‘It does require justice, it does require truth, and it does require prosecution of people who committed terrible crimes,’ he says. If the people in Sri Lanka themselves should find a solution to solve the country’s structural problem, JDS asked Macrae why Sri Lanka itself can’t address what happened in the war.

First and foremost, ever since the war, Sri Lanka has categorically demonstrated that it is neither willing nor capable of carrying out such an inquiry. The UNHRC decided that there have to be an international inquiry, based on the fact that Sri Lanka has demonstrated it could not confront these issues itself. It is clearly understood as a fundamental principle of the UN that if states cannot deal with issues as such as war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide or ethnic cleansing, the international community has a duty to intervene.

The report by the UN on the investigation on Sri Lanka is expected in September and I believe that the high commissioner is committed to that, genuinely. So, the international community and the human rights council, particularly members of the global south has to consider whether the new Sri Lankan government has demonstrated between now and September that they can carry out the next stage which is the judicial process of the accused.

Minimum action to show change

As a minimum, there are things that the Sri Lankan government has to do to demonstrate that it has changed. It should sign up to the International Criminal Court, the Rome Statute. It does not involve any compromise of the sovereignty, because under the Rome Statute, if a country deals with these issues themselves, then the ICC will not intervene.

Secondly, if you are serious about prosecuting crimes against humanity, genocide and ethnic cleansing, then you need to have those crimes built into your penal code. Those do not exist as crimes within Sri Lanka. If they don’t introduce those laws between now and September, then by definition, it cannot conduct a domestic inquiry. Then the UNHRC has to vote for an international judicial mechanism.

Thirdly, there are a series of elements Sri Lanka should demonstrate for a domestic process to even begin to be possible. Those include transforming the situation for the Tamils in the north and the east. As a bare minimum the government should declare who it holds as prisoners and take measures in either releasing or charging them. It should also declare what happened to those who it no longer holds prisoner and compensate their relatives. It includes the ending of the militarization of the north and east. It includes the returning of Tamil lands seized by the army. And indeed, the Northern provincial council should look at returning Muslim lands held by the LTTE. It also should have a mechanism so genuine where witness can give evidence without fear. A law protecting witnesses alone is not enough. As long as the witnesses go in fear an internal judicial process would not be possible.

The bar is very high. Do I think the new Sri Lankan government is capable or willing to carry out those steps? I don’t, I am afraid. I think it is extremely unlikely. Why won’t they carry it out? That comes back to the question of the very profound nature of what is in effect a Sinhala state.

It will be truly wonderful if these transformations do happen. Barring those extraordinary events, there has to be an international process. That process of truth, justice and accountability would be the beginnings of the profound transformation of the situation and would open the way for a genuine process of peace, reconciliation and bold political solutions.

Do you have a guarantee that the international powers are really committed to bringing justice to the people of Sri Lanka?

No. There is no guarantee.

I hope the process which was started last year after going on slowly in the human rights council for many years, reached a significant stage. We shouldn’t underestimate its significance. It was a decision by the UN by definition that Sri Lanka at that time was not willing to launch an independent investigation. Therefore, the UN had to move in. That is not a panacea. No one can guarantee that it would lead to solutions. But, that was an important stage that should be welcomed. It is essential for all those who care about human rights that the international community is not let off the hook and does not let Sri Lanka off the hook. Let’s not drift away from the important step it took last March. It’s by no means guaranteed that the international community will have the courage and conviction to carry this through. That is why it is so important that we keep up the pressure.

Keeping up the pressure

The fact that this is so important to keep up the pressure is why we are still taking this film around the world. The reason why we are translating this film into Sinhala and updating it to English and translating it into Spanish and French, so that it can go to The Group of Latin American and Caribbean Countries in the United Nations (GRULAC), is that we are very, very, very far from the fundamental breakthrough. We are very, very, very far from the point of which we can say we are now well on the way to truth and justice in Sri Lanka. It has never been more important to keep up the pressure. It has never been important that we get this film around the world.

Callum Macrae says that he hopes to hand over a copy of the film to the president of Sri Lanka Maithripala Sirisena in person while the president is in London and to request that any restrictions on watching the Sinhala version of No Fire Zone is lifted.

I am also going to ask the president of Sri Lanka and indeed the media of Sri Lanka to show the film. There should be absolutely no reason for anyone to fear this film being shown on Sri Lankan television. I think it should be shown on Sri Lankan TV, and I am also more than happy to come to Sri Lanka to take part in a live television debate after it has been screened.

Interviewed by Kithsiri Wijesinghe

(jdslanka.org)