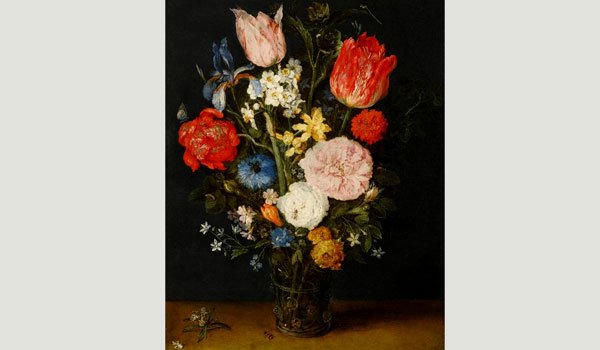

In it, narcissi, chrysanthemums and various other flowers emerge from an improbably small vessel, creating an extravagant spray of colour. Towards the top of the composition, two rounded blooms, each seemingly as plump and soft as a piece of overripe fruit, catch the eye. One is pale pink, the other a dramatic, streaky combination of yellow and red. Both are tulips.

Brueghel’s still life, on loan from a private collection in Hong Kong, is the first painting on view in Dutch Flowers, a new, one-room display at the National Gallery in London. This small, free exhibition charts the course over two centuries of the genre of Dutch flower painting, which Brueghel originated. And tulips figure prominently in many of the 22 ravishing paintings in the show.

“So what?”, you might ask. After all, Dutch artists commonly depicted many other types of flowers, including irises and roses. Yet within the Dutch Republic of the 17th Century, tulips, in particular, were notorious. For this was the age of the so-called ‘tulip mania’, when speculators traded the flower’s bulbs for extraordinary sums of money, until, without warning, the market for them spectacularly collapsed. Ever since, the cautionary tale of tulip mania has been held up as the first example of an economic bubble.

Roots of the problem

When Brueghel was at work on his still life, between 1608 and 1610, this bubble was still decades away from bursting. Brueghel and his specialist contemporaries, such as Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder, painted flowers in order to cater for the new and fashionable interest in horticulture that was preoccupying gentlemen botanists and wealthy connoisseurs. One of their leaders was the pioneering botanist Carolus Clusius, who established an important botanical garden at the University of Leiden during the 1590s.

Clusius also had a private garden at Leiden, and it was here that he planted his own collection of tulip bulbs. At that time, tulips, which originally hailed from the Pamir and Tien Shan mountain ranges in central Asia, and had already been cultivated by besotted gardeners in the Ottoman Empire for decades, were rare and exotic newcomers to Western Europe. They were hard to get hold of, and quickly became desired by other scholars besides Clusius.

Clusius devoted a large proportion of his final years to studying tulips. He was especially interested in understanding how and why, from one year to the next, a particular bulb could suddenly ‘break’. This meant that, inexplicably, it would go from producing blooms of a single colour to flowers boasting beautiful feathery or flame-like patterns involving more than one hue.

Much later, during the 19th Century, it was discovered that this striated effect was actually the result of a virus. But, in the 17th Century, this was still not understood, and so, strangely enough, diseased tulips, emblazoned with distinctive patterns, became more prized than healthy ones in the Dutch Republic. Dutch botanists competed to breed ever more beautiful hybrid varieties, known as ‘cultivars’.

In the early 17th Century, these cultivars began to be exchanged among a growing network of gentlemen scholars, who swapped cuttings, seeds and bulbs both within the Netherlands and internationally. “As that network grew,” explains Betsy Wieseman, the curator of Dutch Flowers at the National Gallery, “it became less of a friendship network, and the scholars started getting requests from people they didn’t know. So they started trading for money. And as that network grew and grew, it became increasingly fragile.”

Strange bunch

The expanding interest in tulips coincided with an especially prosperous period in the history of the United Provinces, which, by the 17th Century, dominated world trade and had become the richest country in Europe. As a result, not only aristocratic citizens but also wealthy merchants and even middle-class artisans and tradesmen suddenly found that they had spare cash to spend on luxuries such as expensive flowers.

Already by 1623, the sum of 12,000 guilders – considerably more than the value of a smart townhouse in Amsterdam – was offered to tempt one tulip connoisseur into parting with only 10 bulbs of the beautiful, and extremely rare, Semper Augustus – the most coveted tulip variety. It was not enough to secure a deal.

When word got out, during the 1630s, that tulip bulbs were being sold for ever-increasing prices, more and more speculators piled in to the market. The intricacies of this market, as well as its frailties, are brilliantly outlined by the historian Mike Dash in Tulipomania: The Story of the World’s Most Coveted Flower and the Extraordinary Passions It Aroused (1999).

One of the curiosities of the 17th Century tulip market was that people did not trade the flowers themselves but rather the bulbs of scarce and sought-after varieties. The result, as Dash points out, was “what would today be called a futures market”. Tulips even began to be used as a form of money in their own right: in 1633, actual properties were sold for handfuls of bulbs.

As people heard stories of acquaintances making unheard-of profits simply by buying and selling tulip bulbs, they decided to get in on the act – and prices skyrocketed. In 1633, a single bulb of Semper Augustus was already worth an astonishing 5,500 guilders. By the first month of 1637, this had almost doubled, to 10,000 guilders. Dash puts this sum in context: “It was enough to feed, clothe and house a whole Dutch family for half a lifetime, or sufficient to purchase one of the grandest homes on the most fashionable canal in Amsterdam for cash, complete with a coach house and an 80-ft (25-m) garden – and this at a time when homes in that city were as expensive as property anywhere in the world.”

Cut flowers

Things came to a head during the winter of 1636-37, when tulip mania reached its peak. By then, thousands of people within the United Provinces, including cobblers, carpenters, bricklayers and woodcutters, were indulging in frenzied trading, which often took place in smoky tavern backrooms. (Drink was a significant factor in the generally intoxicated mood.) Some bulbs even changed hands up to 10 times during the course of a single day.

And then, overnight, the tavern trade disappeared. In early February 1637, the market for tulips collapsed. This was because most speculators could no longer afford to purchase even the cheapest bulbs. Demand disappeared, and flowers tumbled to a tenth of their former values. The result was the prospect of financial catastrophe for many. Disputes over debts rumbled on for years.

The extraordinary thing is that the collapse of the market for tulips didn’t diminish the Dutch appetite for flowers – in art, at least. Dutch flower painting persisted for the best part of two centuries. It is possible to spot tulips in, for instance, Jan van Huysum’s Flowers in a Terracotta Vase of 1736-37. Yet, ironically, very few flower paintings of any sort survive from the 1630s, when the Dutch Republic was in thrall to tulip mania: “There really is this break in production of flower paintings in the 1630s and ’40s,” says Wieseman, “and I can’t quite explain it.” Perhaps, for a few years at least, the excesses of tulip mania, and the traumatic memories of it that followed, were so sickening for Dutch art collectors that they couldn’t stomach the idea of looking at a picture of a flower hanging on their wall.

By Alastair Sooke

-BBC