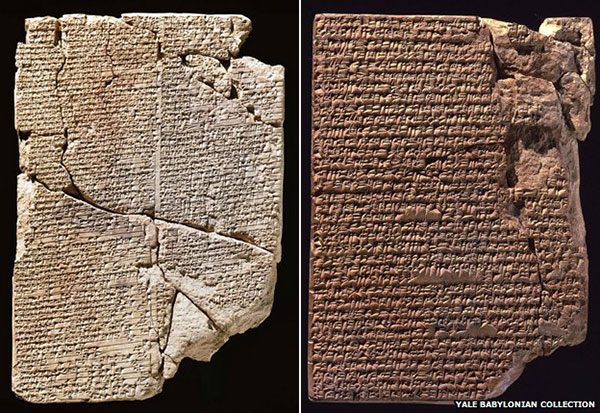

Deep in the archives of Yale University's Babylonian Collection lie three small clay tablets with a particular claim to fame - they are the oldest known cookery books.

Covered in minute cuneiform writing, they did not give-up their secrets until 1985, nearly 4,000 years after they were written.

The French Assyriologist and gourmet cook Jean Bottero - a combination only possible in France, some might say - was the man who cracked them. He discovered "a cuisine of striking richness, refinement, sophistication and artistry" with many flavours we would recognise today. Especially one flavour.

"They seem obsessed with every member of the onion family!" says Bottero.

Mesopotamians knew not just their onions, but also their leeks, garlic and shallots.

And this devotion to the humble bulb is shared by most subsequent cooks too - rare is the cookery book that that is onion-free.

It's the world's most ubiquitous foodstuff. The UN estimates that at least 175 countries produce an onion crop, well over twice as many as grow wheat, the largest global crop by tonnage.

And unlike wheat, the onion is a staple of every major cuisine - it's arguably the only truly global ingredient.

"We think that based on genetic analysis onions came from central Asia, so they are already far afield by the time the Mesopotamians are using them. There's also very early evidence of their use in Europe back to the Bronze Age," says food historian Laura Kelley, author of The Silk Road Gourmet.

"They are a very pretty flower, so it could be someone thought, 'These are gorgeous,' and then found they were also nutritious. They are very, very easy to grow... There's a very good chance of success and very few pests."

Without doubt, onions would have been traded along the Silk Road as far back as 2,000BC, around the time the Mesopotamians were writing down their onion-rich recipes, Kelley says.

Mesopotamian wildfowl pie

Laura Kelley, author of the Silk Road Gourmet, has cooked some of the recipes in the Babylonian cuneiform cookery book, including this pie.

The original ingredients are: Fowl, water, milk, salt, fat, cinnamon, mustard greens, shallots, semolina, leeks, garlic, flour, brine, roasted dill seeds, mint and wild tulip bulbs, says Kelley. (NB the last ingredient can be toxic)

Today, though, there is little global trade in onions. About 90% are consumed in their country of origin. This may be why, in most parts of the world, onions generally escape much notice.

China and India dominate production and consumption - between them they account for about 45% of the world's annual production of more than 70 million tonnes.

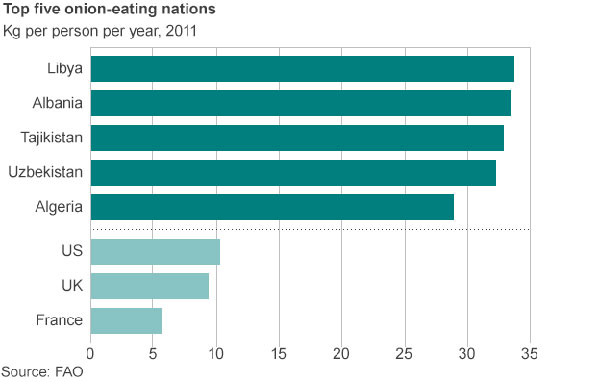

Neither country is among the top onion-eating nations, however, measured by the quantity of onions eaten per head of population. The global champion in this regard is Libya, where in 2011 each person ate, on average, 33.6kg of onion, according to the UN.

"We cook up onions with everything," a Libyan friend tells me. Some even consider macaroni or couscous with onion the national dish.

Kelley points out that a lot of West African cultures eat "huge amounts of onions", though none of them makes it into the UN's top 10.

"There's a Senegalese dish called Yassa, which has a huge amount relative to the amount of meat or veg - it's onions with onions," she says. The Senegalese ate 21.7kg per head in 2011, according to the UN data, more than twice as much as Britons, who got through around 9.3kg per head.

Extended family

The French, whom the British like to think of as big onion eaters, in fact made do with a modest 5.6kg each.

One country where onions do make headlines, is India - if the price goes up too fast, there will be trouble.

Within a month of being sworn-in as India's new Prime Minister in May, Narendra Modi's government intervened to stop onions being exported too cheaply, fearing a rise in domestic prices. Four years ago the government of the day halted all exports, and even imported onions, to prevent street protests.

"There is no established causal relationship, but anecdotally it is true that onion price spikes have become important election issues from time to time," says Pranjul Bhandari, HSBC's Chief India Economist.

Perhaps the most notable impact was in 1998, when the defeat of the governing BJP party in Delhi state elections was put down to the rise in onion prices.

The reason for their political importance is that onions form "an integral part of almost every Indian household's life", according to Bhandari.

"Barring a few exceptions, no Indian meal is complete without onions as an ingredient. As a result, changes in the price of onions are felt every day by the common man," she says.

In the UK, an onion shortage is less likely to cause disturbances, but growers go to some lengths to ensure a steady supply throughout the year.

"Harvest will run through July to September - we know they are ready when they fall over," says Sam Rix, a third-generation onion farmer, growing, packing and supplying onions near Colchester in Essex.

"The onions are stored in warm air at 28C for three weeks to dry them and to help them develop that golden colour. Then they are gradually cooled down to around zero degrees," he says.

"Eleven weeks after harvest the onions will naturally want to grow. It's a race against time to prevent that."

The bulbs are then kept chilled at fridge-like temperatures in warehouses about the size and height of a secondary school sports hall for months on end.

Although this isn't cheap, it helps ensure that something like 90% of the crop gets to market.

Improvements in storage, and the breeding of increasingly hardy varieties means that producers like Rix are now within reach of a tantalising goal - being able to store onions right through until the following year's harvest begins.

"Last year we went into the middle of July with onions that we harvested in September," he says.

He imported onions - from New Zealand and Spain - for just three weeks of the year.

The packing operation, meanwhile, works 363 days out of 365, closing only for Christmas Day and Easter Sunday.

There is a small spike in demand at Christmas - perhaps because few turkey stuffings are made without an onion, or perhaps simply because people eat more at Christmas than at other times of year.

But it turns out that bigger spikes in British onion demand coincide with other religious festivals - Diwali and Eid.

As you might expect, the world's most global ingredient is also its most multicultural.

(BBC News)